Phantom Fury !

Phantom Fury !

#1Phatom Fury, toile de Rober Taylor

http://ep.yimg.com/ca/I/airplanepictures_2064_144069894

Qu'en dites vous ?

Perso, je me demande si ce genre d'attaque contre infrastructures se faisait à la roquette et en radada. D'après mes connaissances sur cette période, la conf' de ces Phantom ressemble plus à du CAS.

j'ai aussi des doutes sur la taille du panier à roquettes qui doit ramponner dans la trappe de train principal ou encore sur le diametre trop faibles des réservors supplémentaires (surtout celui de l'aile droite).

Mis à part qu'il s'agit d'une maginfique peinture, qu'en dites vous ? Est-ce que ces détails vous choquent ?

V.

http://ep.yimg.com/ca/I/airplanepictures_2064_144069894

Qu'en dites vous ?

Perso, je me demande si ce genre d'attaque contre infrastructures se faisait à la roquette et en radada. D'après mes connaissances sur cette période, la conf' de ces Phantom ressemble plus à du CAS.

j'ai aussi des doutes sur la taille du panier à roquettes qui doit ramponner dans la trappe de train principal ou encore sur le diametre trop faibles des réservors supplémentaires (surtout celui de l'aile droite).

Mis à part qu'il s'agit d'une maginfique peinture, qu'en dites vous ? Est-ce que ces détails vous choquent ?

V.

Frenchie

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

#2

Les deux réservoirs ont l'air complètement différents, une explication ?Frenchie a écrit : encore sur le diametre trop faibles des réservors supplémentaires (surtout celui de l'aile droite).

V.

"Tu as peur, Boyington, tu refuses le combat" (Tomio Arachi).

-

Warlordimi

- Pilote émérite

- Messages : 9121

- Inscription : 15 mars 2004

#3

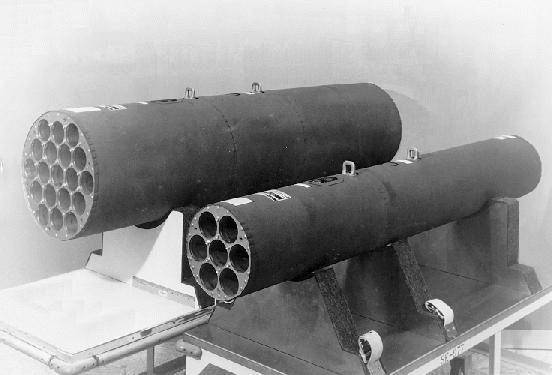

Le pod roquettes est un LAU32/A de 7 roquettes de 70mm. Son utilisation, je laisse aux plus cultivés.

Ce qui me dérange perso, c'est le nez. Difficile de voir si c'est un F4D ou F4E. Si F4D, s'aurait pu être un pod canon SUU23.

Sinon, je pense que c'est juste un problème de perspective. Le réservoir droit devrait être plus gros!

Ce qui me dérange perso, c'est le nez. Difficile de voir si c'est un F4D ou F4E. Si F4D, s'aurait pu être un pod canon SUU23.

Sinon, je pense que c'est juste un problème de perspective. Le réservoir droit devrait être plus gros!

#4

Il y a plusieurs choses qui me choquent, en effet

- L'armement n'est adapté ni à la mission ni à l'avion

- L'explosion se produit derrière, donc c'est une charge non propulsée. Si ce n'est pas lui, quel intérêt de passer au dessus et si près ? Si c'est lui, où sont les pylones des bombes en question ?

- Le canon est étrange. Le E a un carénage carré, or celui ci est rond. Je ne connais pas de modèle avec un canon comme ça.

- Au niveau du dessin proprement dit, il y a un problème entre l'angle de l'aile droite et celui de la derive : la première partie est pratiquement horizontale (quand l'avion est à plat) et doit faire un angle de 90° par rapport à la dérive. Là, on dirait que l'aile à un dièdre.

Ceci dit, ce sont des erreurs de conception, mais la peinture elle-même est très bien faite.

- L'armement n'est adapté ni à la mission ni à l'avion

- L'explosion se produit derrière, donc c'est une charge non propulsée. Si ce n'est pas lui, quel intérêt de passer au dessus et si près ? Si c'est lui, où sont les pylones des bombes en question ?

- Le canon est étrange. Le E a un carénage carré, or celui ci est rond. Je ne connais pas de modèle avec un canon comme ça.

- Au niveau du dessin proprement dit, il y a un problème entre l'angle de l'aile droite et celui de la derive : la première partie est pratiquement horizontale (quand l'avion est à plat) et doit faire un angle de 90° par rapport à la dérive. Là, on dirait que l'aile à un dièdre.

Ceci dit, ce sont des erreurs de conception, mais la peinture elle-même est très bien faite.

(\_/)

(_'.')

(")_(") "On obtient plus de choses avec un mot gentil et un pistolet qu'avec le mot gentil tout seul" Al Capone.

Mon pit

(_'.')

(")_(") "On obtient plus de choses avec un mot gentil et un pistolet qu'avec le mot gentil tout seul" Al Capone.

Mon pit

#5

Le ventre du réservoir est blanc...sur fond clair : On a tendance à ne voir que la partie sombre ce qui donne au réservoir une apparence plus fine (?)

In tartiflette we trust

#6

- C'est clair c'est pas un F-4 E, c'est un IRST pas un pod canon.

- Les rockets je pencherais plutôt pour des Zuni de 127 mm, dans ce cas c'est adapté à l'attaque d'infrastructures.

- Pour le passage vertical ça fait plus joli.

- Le bidon droit est trop petit

- La critique est facile, l'art...

- Les rockets je pencherais plutôt pour des Zuni de 127 mm, dans ce cas c'est adapté à l'attaque d'infrastructures.

- Pour le passage vertical ça fait plus joli.

- Le bidon droit est trop petit

- La critique est facile, l'art...

#7

jojo a écrit : - La critique est facile, l'art...

Bah... c'est pas moi qui vais te dire le contraire !

Merci pour les infos sur les Zuni de 127mm, ça donne plus de sens.

Dans son approche, Robert Taylor travaille avec des pilotes pour qu'ils signent les prints... donc on peut imaginer que ce n'est pas trop déconnant. Maintenant je ne trouve pas que cette peinture soit de son niveau habituel.

Frenchie

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

#8

En fait la dernière remarque ne s'adressait pas vraiment à toi, c'était juste pour pas parraitre trop prétentieux:sweatdrop.

En France on avait les Thomson de 100mm sur Jag (pod de 4), utilisées au Bosnie il me semble.

En France on avait les Thomson de 100mm sur Jag (pod de 4), utilisées au Bosnie il me semble.

-

SpruceGoose

- Pilote Confirmé

- Messages : 3492

- Inscription : 31 octobre 2003

#9

Cette toile représente une attaque de l’été 1972 conduite par Steve Ritchie au cours d’une opération FAST FAC Linebacker.

L’avion est un F4D du 555th TFS.

De toute façon, sans le pitot visible, ce ne peut pas être un E.

Non plus car le nez est trop court, de plus la partie noire du nez du E est très loin du pare-brise…

A propos des FAST TAC !

* * *

L’avion est un F4D du 555th TFS.

De toute façon, sans le pitot visible, ce ne peut pas être un E.

Non plus car le nez est trop court, de plus la partie noire du nez du E est très loin du pare-brise…

A propos des FAST TAC !

Quand à savoir un LAU-32 ou LAU-59, ça dépend de la roquette employée...Major John M. Scanlan, USMC

Currently, the Marine Corps employs the F/A-18D as a fast forward air controller, or FastFAC, to control strike aircraft. The term FastFAC emerged from Vietnam and merely referred to the speed provided by jet engines when compared to the turboprop engines of slower observation aircraft. However, beyond the Fire Support Coordination Line (FSCL), the FastFAC does not control CAS like a typical Ground FAC. This is because there are no friendly forces on the ground. Instead, the FastFAC controls interdiction sorties dedicated to shaping the battlefield for future operations. Therein lies the argument: in the FastFAC designation, the “FAC” portion is a misnomer, for it implies that ordnance is being delivered from CAS aircraft in close proximity to Marines on the ground. Thus, I have coined the non-doctrinal term “FastDAC”, for fast deep air controller. My FastDAC will define a tactical jet controlling interdiction aircraft beyond the FSCL.

Though it was not labeled as such, the FastDAC first proved to be relevant in Vietnam and absolutely vital in Operation Desert Storm. However, during these conflicts, FastDAC was conducted “on the fly”, because neither the Marine Corps nor the Air Force possessed adequate doctrine. Because the role was not defined, the lack of doctrine made training for the mission an impossibility.

Thus, this article will argue three contentions. First, U.S. aviation forces relegated the FastFAC mission to tactical jets doing on-the-job training (OJT) during Vietnam and Operation Desert Storm. Second, the Marine Corps must embrace the concept of VMFNA squadrons conducting FastDAC. Lastly, the Marine Corps’ lack of doctrine is setting the stage for the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) to potentially do FastDAC OJT on the future battlefield. OJT will fail to keep pace with the tempo of operations in 2010.

Vietnam

In Vietnam, three problem areas emerged in airborne air control: target identification, fratricide, and the survivability of the controlling aircraft. These problems were a function of the type of aircraft that did the controlling. Flying lower and slower allowed propeller-driven FAC aircraft to accurately identify targets and avoid fratricide; however, such aircraft were not survivable. Flying higher and faster made jet aircraft more survivable; however, those capabilities complicated target identification and increased the potential for fratricide. This is the compromise in jet airborne air control. The development of this compromise began in 1965 at Soc Trang.

In Vietnam, the nature of guerrilla warfare placed a premium on surveillance and reconnaissance. Initially, the Cessna O-1s assigned to HMM-362 at Soc Trang bore that burden. As an interim solution to the shortage of these small, slow, propeller-driven aircraft, the Pentagon filled the void in 1967 with the purchase of the Cessna O-2A [1] A year later, the next generation of aerial observation aircraft arrived at Da Nang, with the new OV-10As assigned to VMO-2.

Two developments led to the Marine Corps’ abandonment of the “low ‘n’ slow” O-1, O-2, and OV-10. The first was the increased number of interdiction missions required in two particular areas: the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the coastal region of North Vietnam. The second development was the growing lethality of an air defense system employing Soviet surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA).

To counter these two developments, the Marine Corps devised the FastFAC in 1966, employing two-seat F-9 fighter/attack jet aircraft. [2] However, the Marine Corps possessed no doctrine for this new mission, which meant that aviators could not effectively train. Thus, FastFAC advocates proceeded with OJT. However, the Marine Corps wrongly labeled this new mission as Airborne Tactical Air Coordinator, or TAC(A). Previously, the TAC(A) mission was strictly the OV-10’s bailiwick, due to its lengthy endurance and strong communications suite. The Marine Corps wrongly assumed that since the F-9 was replacing the OV-10, the F-9 could do the OV-10 TAC(A) mission. But this new FastFAC mission, mislabeled as TAC(A), was actually the origin of the FastDAC. The intent of the F-9 was to control interdiction sorties beyond the FSCL.

In August of 1967, the TAC(A) role was relegated to the new two-seat TA-4F. The title of this FastDAC mission was altered to VR/TAC(A), with the VR representing visual reconnaissance. However, the TAC(A) misnomer remained, and there were still no formal procedures or training. A step in the right direction occurred with the establish-ment of a 7-10 day exchange program with Air Force F-100 pilots at Phu Cat who were experimenting with the same mission. In 1969, the “Playboys” of Headquarters and Maintenance Squadron Eleven (H&MS-11) finally standardized the mission using a 1968 manual of Standard Operating Procedures (SOP).

While Marine Aviation unknowingly struggled with the FastDAC concept, the USAF experienced the same difficulties. Initially, Air Force FACs flew the same O-1,

O-2, and OV-10 aircraft as the Marine Corps. Thus, it is not surprising that they were replaced with tactical jets for the same two reasons: the inability to range the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the increased surface-to-air threat. The introduction of high performance jets to control interdiction aircraft -- and not CAS aircraft -- required a complete change in the mission. Airborne air control was quickly evolving into FastDAC.

This change in mission led to the Air Force FastFAC. Code named “Misty”, the initial FastFAC missions were flown by two-seat F-100F Super Sabres in June of 1967. [3] These pilots were strictly volunteers, and usually experienced combat veterans. Foregoing the opportunity to ever shoot down a MiG, these hardy volunteers dedicated themselves to one of the most dangerous missions of the Vietnam War . [4] In March of 1968, 7th Air Force Headquarters ordered F-4s from the 366th Tactical Fighter Wing (TFW) to be tested as FastFAC platforms. F-4 pilots went to Phu Cat and flew five missions in the rear seat of the F-100F, while the Misty back-seat FACs went to Da Nang for three flights in the F-4. These F-4 FastFAC missions were code named “Stormy”, and tactics differed very little from those of the Misty FastFACs. This validated that the compromise of jet airborne air control still held true.

The limited success of the Air Force’s FastFAC experiment was attributed to one thing: a poor choice in aircraft. The flight characteristics of the F-100 and the F-4 were no comparison to the TA-4F’s slick combination of visibility, speed, and maneuverability. Second, the Air Force was slow to embrace the FastFAC concept. The Marine Corps’ 1966 jump start with the F-9 was a full year ahead of the Air Force’s 1967 Misty Program. However, the Air Force was first in establishing FastFAC doctrine. Whereas the Marine Corps plagiarized an old H&MS-11 SOP in 1969 to standardize FastFAC procedures, the Air Force had already published the 366th TFW Operation Plan 10-68 in September of 1968. This doctrine outlined Stormy procedures for VR, strike control, Bomb Damage Assessment (BDA), training, crew coordination, and operating minimums. [5]

Lessons from Vietnam

In 1973, the Joint Technical Coordinating Group for Munitions Effectiveness at the Naval Weapon Center, China Lake, formed a Target Acquisition Working Group (TAWG) for the specific purpose of studying airborne air control. To obtain data, the TAWG sent questionnaires to airborne FACs from Vietnam, to which twenty-four Marine Corps and fifty Air Force aviators responded. Unfortunately, only two with FastFAC experience replied, one from each service. The report confirmed what had been so sadly demonstrated in Vietnam: formal training in FastFAC procedures was not present in Marine or Air Force training programs. The lone Air Force FastFAC respondent admitted that his unit consisted of volunteers who received OJT.

Concerning the TAWG survey, the compiled results from both services were amazingly similar. Both the Marine Corps and the Air Force experienced the same difficulties in conducting the airborne FAC mission. However, the weak response from those with FastFAC experience clearly implied that the shared experiences reported by the TAWG were in conducting airborne forward air control (FAC(A)),and not FastFAC.

For all airborne FACs who returned the survey, the most difficult aspects of the mission were target location and strike execution. [6]. First consider target location. Since ninety-seven percent of the respondents were FAC(A)s who flew low and slow to identify targets, a logical assumption would be that some factor other than the FAC(A)’s altitude and airspeed prevented his locating the target. This assumption was validated by the questionnaire’s follow-on inquiry: “what prevented target idenÌ‹ cation?” The four most common reasons were the target being completely hidden by foliage or obscured by foul weather , or the friendlies not knowing or being unable to mark their position. It is reasonable to assume that these same failures would have occurred for a FastFAC under the same conditions.

Next, consider the difficulty in strike execution. Here, the one most common reason for failure was the enemy’s ability to withdraw before the attack could be executed. That is a sad indictment of the Command and Control (C2) system employed in Vietnam. Respondents repeatedly asserted that the lack of a quick response to their air request was their greatest disappointment. Some stated that the minimum amount of time from strike request to aircraft check-in was one hour. At even a moderate walking pace, this allowed the enemy to evade an attack as long as foliage concealed his departure. Since FastFACs operated as single aircraft and carried no air-to-ground ordnance, this same failure would have hampered both Marine Corps and Air Force FastFACs.

A better source of FastFAC effectiveness is found in a 1969 CHECO report entitled Jet Forward Air Controllers in SE Asia. This document is more applicable than the TAWG survey because it specifically examined jet forward air controllers. This CHECO report called using jets as FACs an “experiment” and deemed it to be a success. By September of 1968, enough data had been compiled from the Air Force’s Misty experiment to confirm the value of the FastFAC. The CHECO statistics compared the results of strike aircraft on an armed reconnaissance mission without a FastFAC against those of strike aircraft who attacked a target under FastFAC control. The chances of confirmed BDA doubled when a FastFAC was present. The average FastFAC sortie resulted in a .97 BDA occurrence; whereas strike aircraft alone achieved a .41 BDA occurrence. [7] Armed reconnaissance air strikes were less than half as effective when conducted without a FastFAC. These results laid dormant for twenty-three years, until the services of the FastDAC were required once again.

* * *

#10

Merci Spruce pour l'explication FAST FAC, je viens de tomber sur le sitequi explique l'idée générale. pour le Fast Fac, cela explique un peu mieux la conf'.

Frenchie

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

-

SpruceGoose

- Pilote Confirmé

- Messages : 3492

- Inscription : 31 octobre 2003

#12

* * *A Day In The Life Of A Fast FAC

By Shelby G. Spires

Streaking along, strapped into an F-4, above a Southeast Asian river, in 1972, L.D. Johnston noticed something was out of place. An off color had caught his eye, and as a good fighter pilot/forward air controller the then first lieutenant decided to check it out.

He flew multiple passes through the deep canyon looking for something out of the ordinary.

"I kept getting lower, and I could tell with each pass that something was going on " I could see a little bit more detail to it," said now Brig. Gen. Johnston.

Flying as low to the river as possible, Johnston had seen a small barge on the river. When he returned from a pass, the barge was gone. The barge was his clue that the enemy was hiding something off the side of the river.

"In a couple of minutes it was gone, and I knew there was a pull off somewhere along the river. As I flew down the river and I went right by this great big cave."

The cave was well camouflaged and the boat and possibly other war materiel was in it, said Johnston. "So I pulled up and came back around to mark it as a target," the general said. "I fired the first rocket and it went into the cave and no smoke appeared. It went to far back into the cave. So I came back around figuring that would never happen again, but it did. The smoke rocket again went too far into the cave."

On the third marking pass, threading his way between canyon walls and riverbeds, Johnston fired a rocket which hit the side of the cave wall putting up a wall of smoke so the target could be bombed.

"Two Navy A-6s came in and put some thousand pounders on it. It was one of the best bombing passes I had ever seen," said Johnston. "These guys laid these thousand pounders right inside that cave."

The 1,000 pound bombs did the trick -- pulverizing the barge and the contents of the cave. "There was ammo in there too, and it blew along with the barge. The top of the cave was blown off, and the sides just disintegrated. There was nothing left."

During the Vietnam War, Johnston's was the job of a jet fighter pilot blended with a forward air controller, or Fast FAC, he marked targets, controlled air strikes and found targets all from the front seat of an F-4. Finding the cave, marking it and setting loose two Navy aircraft on it is a prime example of what a forward air controller did on a daily basis.

In Southeast Asia, the FAC had two general roles: support troops on the ground who were fighting off enemy soldiers and try to find targets to destroy with air strikes.

The basic concept of Fast FAC was fulfilling the requirement for forward air controllers in a high threat area. Many FACs during the early part of the war and in the lesser threat areas used smaller, single engine propeller driven aircraft such as the O-1, O-2 and OV-10, which were very vulnerable to just small arms fire.

"Well that worked find in the lesser threat areas of South Vietnam and Laos," said Johnston. "When you would get into North Vietnam when the threat was very high from ground fire, anti aircraft, surface-to-air missiles and even MiG aircraft, then you really couldn't put one of these slow moving propeller aircraft into that arena, but you still had the requirement for targets to be found and marked."

What was needed, Air Force planners surmised, was an aircraft that would be able to take on gun and SAM sites, and either hold its own or be fast enough to run from the MiGs. Naturally, that would be a jet fighter and not a prop observation plane. To fill the need the Fast FAC concept was born. Named Fast because of the speed of the jets and beginning in 1965, aircrews used two seat versions of the F-100 "Super Sabre," but as the war progressed another platform was needed, and the Air Force turned to their newest fighter the McDonnell Douglas F-4 "Phantom II."

"What made the F-4 an ideal platform for this, somewhat like the two seat F-100, was because the F-4 having both a pilot in the front seat and a navigator in the backseat gave you two sets of hands, eyes and brains to effect the kind of target search and coordination with the other fighter bombers."

In World War II the goal for fighter pilots was to become an ace " shoot down five aircraft. In Vietnam there was little chance of ace status happening for pilots and aircrews because of political restrictions and a '69-'72 North Vietnam bombing halt which kept North Vietnamese and American fighter pilot battles to a minimum. It was only natural that the fighter pilots would gravitate toward something with a challenge. The Fast FAC program was just that.

The program was an elite set up, said Col. Billy Diehl, who flew as a navigator in the back of the two man F-4 during the Vietnam War. "There were a lot of guys who wanted to get into the program," he said. "It was something where you felt like you made a difference in doing it. You were contributing to the war effort in that you were putting a lot more ordinance on targets than just what was on your particular aircraft."

The FAC programs, or shops, were installed at most fighter bases in Thailand. Johnston and Diehl worked out of Korat Royal Thai Air Base, Thailand and were Tiger FACs. Other FAC shops were the Wolf FACs at Udorn, Thailand, the Laredo FACs at Ubon, Thailand and the Stormy FACs who worked out of Da Nang, South Vietnam.

The wings would pull the best pilots and navigators out of the three squadrons.

Being a Fast FAC meant a aircrews were noted as some of the best in the theater, and the sentiment meant a lot to some of the FAC crews, said R.C. Gravlee, who flew as a Laredo Fast FAC as a pilot/navigator in the backseat of an F-4 in 1970.

"The satisfaction level of doing that, of contributing to the war effort was immense compared to some missions where you would just go to a place where a supposed truck park was and blow up a few trees," said Gravlee, "You were doing something."

The FAC shops tagged five pilots and four navigators to work in the programs, said Johnston. "You had small cadres that was selected from the squadron and they were able to concentrate on certain parts of the theater and be knowledgeable about what went on in those areas from day-to-day," said Johnston.

In Johnston and Diehl's squadron, the older more experienced FACs were given the nickname of "Papa Tiger" and as such was the official leader of the FAC shop.

"You wanted guys with experience. Experience flying the aircraft and flying in combat," said Gravlee. "Generally, it took about six months of flying to even be considered for the program."

Diehl and Johnston, who command the 347th Wing, flew as a team on some of the FAC missions. Although they were not teamed together permanently. "You didn't always work together with the same people," said Diehl. "And we didn't always do FAC work. Sometimes we would be used on a regular strike mission."

The FACs flew in the same areas doing what they called VR work, or visual reconnaissance, and as such kept a mental, daily picture of what was suppose to be where, said Diehl.

"The beauty of the Fast FAC or any kind of FAC program is that you get so familiar with your area and you will notice what is out of the ordinary," said Diehl. "That's why you had guys working the same places all the time. They had to know the surrounding terrain in order to realize what was out of place."

Diehl added a favorite target of many pilots were the antiaircraft sites, which dotted important targets. Dueling with the guns was a fools errand in many situations, no matter how personally rewarding. "Most guys liked to attack guns ... but it didn't do much for the war effort," he added .

The Fast FAC missions were some of the longest and most dangerous Johnston and Diehl ever encountered, the two military pilots said. "They were exponentially more dangerous than a regular strike mission," said the general.

The life expectancy of a Fast FAC wasn't a positive figure. Because they worked in high threat areas, and initially worked with just one aircraft, the FAC program was very dangerous. "The figures I heard at the time was that you were 25-times more likely to be shot down as a Fast FAC than doing a regular job," said Johnston. The dangers were readily apparent to the general. On his first Fast FAC mission Johnston was shot down.

To counter the threats, the FACs developed survival guidelines, said Diehl. "We had a rule of fives " 5-gs on the aircraft, 5,000 feet altitude and keep about 500 knots speed," he said. "Due to the job, of getting low and identifying targets you couldn't always keep to those, but it was a benchmark."

The benchmarks meant pilots kept pulling the plane into tight turns -- 5-gs, flew above small arms range -- 5,000 feet, and flew fast -- 500 knots, all of which kept them safer from the ground gunners.

"To counter those guys on the ground you just kept pulling into a tight turn, and jinking " varying your altitude," said Gravlee. "They couldn't get you. It would spoil their aim."

The missions were not only dangerous, but were also longer than the normal 90 minute or two hour strike flights pilots normally pulled, said Diehl.

"Sometimes we would refuel five times, and there was a lot of communication back and forth between us and the airborne central command and control aircraft (ABCCC) ... the back seater would free up the front seater to look out and see what the target was and who was shooting at him basically we worked the maps and navigation and coordination with ABCCC and we did a lot of secretarial work with all of that."

The guy-in-back was responsible for keeping up with navigation charts, strike data and generally monitoring a lot of details associated with getting from point A to point B. "The back seat sometimes resembled an office full of papers," Diehl said and laughed. "We had to keep up with a lot of things in the aircraft."

Did the hard work, dangers and frustrations bother Johnston and Diehl?

"We were young lieutenants. I never gave it much thought. We wanted to get down amongst them and do our jobs," said the general.

"It was our job," echoed Diehl. "Sure you were scared sometimes, but ours was the life of a soldier. My country was at war, and this was my job. I never thought about it outside of mentally preparing myself for the technical side of what it was I had to do."

-

Pink_Tigrou

- Pilote Confirmé

- Messages : 2566

- Inscription : 14 septembre 2005

#14

D'un point de vue personnel, et sans préjuger de la qualité technique ou de la réalité historique, je trouve à cette toile autant de profondeur qu'un film de Steven Seagal...

#15

Celle que présente Kaos est saisissante. Mais celle qui fait l'objet du post initial me donne juste une impression de non-séduction. Je ne sais dire pourquoi. Par contre, pour l'explosion, il peut s'agir d'une passe roquette à grande vitesse suivie d'un survol direct tandis que survient une explosion secondaire. Ca ne me choque pas.

-

Corktip 14

- Pilote Confirmé

- Messages : 4240

- Inscription : 16 août 2003

#16

Quand au pod, pour moi c'est bien des Zunis de 127mm, et le pod en lui-même serait, dans ce cas, un LAU-10A.

#17

Pas d'accord.Corktip 14 a écrit :Quand au pod, pour moi c'est bien des Zunis de 127mm, et le pod en lui-même serait, dans ce cas, un LAU-10A.

Le pod sur la toile semble avoir au moins cinq, si ce n'est pas six emplacements.

Un LAU-10/A, c'est quatre roquettes.

Par ailleurs, c'est un armement USN/USMC, et non pas USAF.

Je ne me rappelle pas en avoir déja vu sous un Phantom II USAF.

-

Warlordimi

- Pilote émérite

- Messages : 9121

- Inscription : 15 mars 2004

#20

Talking proudThis is "Chico the Gunfighter," F-4E-37-MC 68-0339 at the Danang arm-dearm area prior to her special Fast FAC mission. The 366 TFW Commander, Col. George W. Rutter, is aboard.

A priori le seul F-4E de l'époque modifié de manière à pouvoir emporter des rockeye.

Le site des misty

Les bouquins sont excellents, quoique pouvant être indigeste vu les briques que ce sont.

-

SpruceGoose

- Pilote Confirmé

- Messages : 3492

- Inscription : 31 octobre 2003

#21

Si la mission est du Fast FAC, donc marquage de cible, il est probable que la roquette soit une WP de 2.75 inch (White Phosphorus – tête Mk67 ou M156).Frenchie a écrit :

j'ai aussi des doutes sur la taille du panier à roquettes qui doit ramponner dans la trappe de train principal.

Support à 7 roquettes sur la toile de Robert Taylor.

La longueur moyenne de la roquette en question est d’environ 1.60 mètre.

Le support LAU-xy (un peu plus long) ne gêne absolument pas les trappes de train. Il y a beaucoup de marge.

Pour l’année 1972, c’était probablement un LAU-32 ou un LAU-59.

EDIT : Apparemment un LAU-59 car selon mes docs, on installait 1 seul LAU-59 sur le support d'aile interne - et/ou plusieurs LAU-32 sur le support d'aile externe.

Infos :

USAF

Supports à 7 rockets (2.75 inch) possibles : LAU-32 LAU-49 LAU-54 LAU-56 LAU-59 LAU-68 LAU-91 LAU- 94 et LAU-131

US Navy et USMC :

Une Zuni (5 inch) mesure environ 1.95 m de long. Le support LAU-10 (4 roquettes / un peu plus long) monté sur le point d’attache d’aile ne gêne absolument pas les trappes de train. Il y a là aussi beaucoup de marge.

* * *

#22

Merci Spruce pour toutes ces précisions.

malgré tout, je ne suis pas trop emballé par l'ensemble. Puis j'ai toujours ce problème de réservoir supplémentaire et d'IR seeker sous le radome qui ressemble à la bouche de canon du F4E.

La "military Gallery", éditeur de taylor, dit que cette peinture est restée en attente pendant un certain moment dans l'attente d'infos techniques, notamment sur le pod roquettes. Interessant non ?

malgré tout, je ne suis pas trop emballé par l'ensemble. Puis j'ai toujours ce problème de réservoir supplémentaire et d'IR seeker sous le radome qui ressemble à la bouche de canon du F4E.

La "military Gallery", éditeur de taylor, dit que cette peinture est restée en attente pendant un certain moment dans l'attente d'infos techniques, notamment sur le pod roquettes. Interessant non ?

Frenchie

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

#23

Un petit lien, ça ne fait pas de mal.

Le nez du F-4 en question ne me choque pas trop, faut vraiment s'appeler Dimitri pour le confondre avec un F-4E (Oui, je sais c'est gratuit mais ça fait du bien!:Jumpy:).

Je me souviens avoir acheté un jour un des recueils de R. Taylor, c'est un véritable plaisir à feuilleter.

Frenchie, toi qui es de la partie, tu n'aurais pas un lien vers un éditeur orienté Armée de l'Air?

Le nez du F-4 en question ne me choque pas trop, faut vraiment s'appeler Dimitri pour le confondre avec un F-4E (Oui, je sais c'est gratuit mais ça fait du bien!:Jumpy:).

Je me souviens avoir acheté un jour un des recueils de R. Taylor, c'est un véritable plaisir à feuilleter.

Frenchie, toi qui es de la partie, tu n'aurais pas un lien vers un éditeur orienté Armée de l'Air?

#24

Absolument, Taylor est un des meilleurs, aucun doute là dessus. Autant je pense qu'il est impabatble pour les sujet WWII? autant sur la période moderne je le trouve un peu en dessous de son art.III/JG52-Freiherr V. Kaos a écrit :Je me souviens avoir acheté un jour un des recueils de R. Taylor, c'est un véritable plaisir à feuilleter.

Frenchie, toi qui es de la partie, tu n'aurais pas un lien vers un éditeur orienté Armée de l'Air?

Bref... c'était intéressant de voir ce que vous en pensiez.

Pour les éditeurs d'aviation art sur l'Armée de l'Air, je n'en connais pas. Il y a la folie de la BD aéro en ce moment qui occupe pas mal les éditeurs. On est tres loin en France / Belgique / Suisse de l'engouement sur les poster / prints que l'on rencontre dans les pays anglo saxons.

Tu peux aller sur Aviation Illustréeet contacter les artistes qui te plaisent, il y a beaucoup de sujets Armée de l'Air et dans des styles très différents.

Pour le prix d'une reproduction de taylor, tu pourras sans doute t'offrir un original ...

L'autre source pourrait être le site des Peintres de l'Airmais il est assez peu documenté. Là les originaux seront plus cher.

Frenchie

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

https://www.toilesvolantes.com/

-

Warlordimi

- Pilote émérite

- Messages : 9121

- Inscription : 15 mars 2004

#25

'foiréIII/JG52-Freiherr V. Kaos a écrit :Un petit lien, ça ne fait pas de mal.

Ya un trou!!!! Que je ne suis pas le seul à avoir remarqué soit dit en passant

PS: 'foiré